CBI Struggles With Rising Caseload & Limited Manpower

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s 'lead’ federal investigative agency, often draws flak for not being an autonomous institution. Despite that, the CBI is often the 'go to’ agency for high-profile cases.

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s 'lead’ federal investigative agency, often draws flak for not being an autonomous institution. Despite that, the CBI is often the 'go to’ agency for high-profile cases.

The problem is that despite the caseload increasing in size and profile, the number of officers tasked to solve the cases is still not enough. Now, that might be the problem with the overall law and order machinery in India but is no less acute with the CBI.

An example of recent cases registered with the CBI would be one over allegations of bribery in the procurement of 12 Augusta Westland 'VVIP’ helicopters and the murder of a Deputy Superintendent of Police in Pratapgarh, Uttar Pradesh.

On an average, the CBI takes in more than 1,000 cases (1,119 in 2009 and 1,009 in 2010) every year. Or around 80 cases per month. And there are close to 10,000 cases pending trial at this point (2011 data). Recent data shows that CBI registered 1,003 cases in 2011.

Where did they come from? Turns out that 79 were taken up at the request of the State Governments, 122 on the directions of courts, 838 were regular cases and 154 were preliminary enquiries.

At end-2011, around 828 cases were pending investigations, charge-sheets were filed in 701 cases and 895 court cases received judgements. Of these, 497 cases resulted in conviction and 209 in acquittal. The conviction rate of the CBI was 67% around 2011.

Some notable charge-sheets during 2011 was against a senior IRS officer who fraudulently obtained Rs 90 crore from National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) and against the Health Secretary of a state government for dishonestly purchasing medicines worth Rs 130 crore without actual requirement.

And a state-owned and run All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) admission racket where private persons rigging admission process for the entrance exam was busted and a scam connected with the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi involving alleged kickbacks made to senior officers and politicians for supply of equipment and services.

Interestingly (or maybe not) most cases registered with the CBI are to do with disproportionate assets of Government officials. The rest span anti-corruption, economic offences and special crimes (murders, terrorism etc)

Now to look at the CBI’s manpower challenge. Here are the gaps.

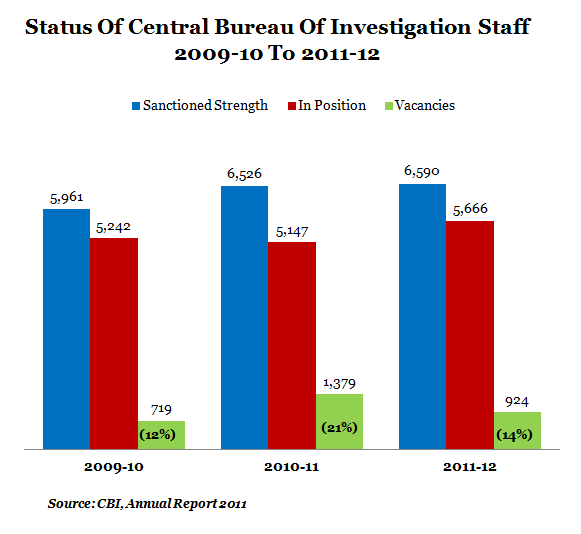

Figure 1

The vacancies were the highest in 2010 (21%), and the average vacancies were about 16% during the period 2009-11.

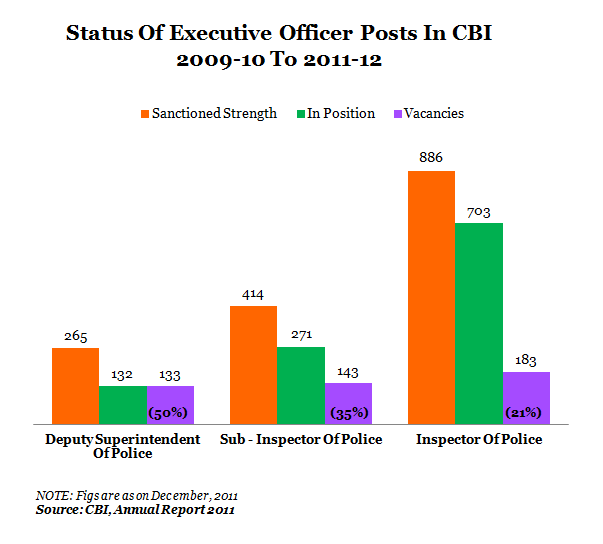

The vacancies may not be high enough to affect the organisation adversely but it is the executive officers’ positions (executive officers are inducted from the Indian Police Service or through competitive examinations) that are mostly vacant:

Figure 2

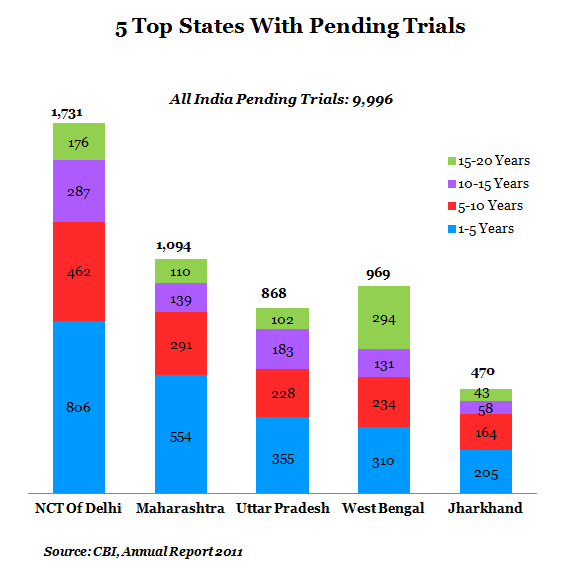

Another issue that plagues the CBI are the state-wise pending cases. Table 3 gives the idea of the top 5 states with pending trials:

Figure 3

Incidentally, out of the total of around 10,000 pending trial cases, more than 1,000 cases are pending trials for 15-20 years. NCT of Delhi accounts for 17% of the total pending trial cases. The CBI documents do not give the reasons for so many pending trials

And does the CBI have the resources, or put another way, to what extent is it resourced? The agency has been allocated Rs 462 crore in 2013-14, up 14% over 2012-13 when it was allocated Rs 405 crore.

A look at the 2011-12 balance sheet shows that construction and renovation of office buildings alone took up Rs 28 crore. This was the same time a brand new CBI HQ was built in Delhi at a cost of Rs 201 crore.

So, vacancy in executive posts and high pending trials are crucial issues that need to be sorted out before CBI is burdened with an average of 80 cases per month.